This can lead to truly hilarious questlines like ‘Claptrap’s Birthday Bash’ in Borderlands 2 or potentially heartbreaking quests like Witcher 3’s ‘The Last Wish’.įollowing the main quest in open world RPGs singularly will lead to a multitude of issues. Except these RPGs also encourage and actively require you to get distracted and do other things.

#Spec ops the line loading screen quotes series#

A series of main questlines, or perhaps a singular quest to follow and complete inevitably saving the world. Most open world games, especially RPGs, have the ‘impending doom’ main storyline. But CDPR’s games like Witcher 3 and Cyberpunk 2077 inherently, and perhaps unavoidably, have this problem of ludonarrative dissonance. Could probably handily win GOTY most years (except 2020, because The Last of Us Part 2 exists). Now, before I start, I want to clarify I think The Witcher 3 is a stunning RPG in almost every way. Open world titles, a trend I famously have issues with anyway, struggle tremendously with ludonarrative dissonance. It’s become something of a ‘buzzterm’ (a term I, in fact, just made up) over recent years with the continual expansion and increasing scope of open world video games. The criticism drew so much attention that Naughty Dog added a trophy called “Ludonarrative Dissonance” in Uncharted 4 for killing 1000 enemies. So much so that it’s actually pretty easy to forget that through the four games that he features, he kills thousands of people without a second (or probably even first) thought. The cutscenes and the narrative throughout each game unequivocally make him the good guy. The protagonist of the mainline series, Nathan Drake, is painted as charming, witty, loyal, funny, and just a general delight to be around. The most famous example is the Uncharted series on PlayStation.

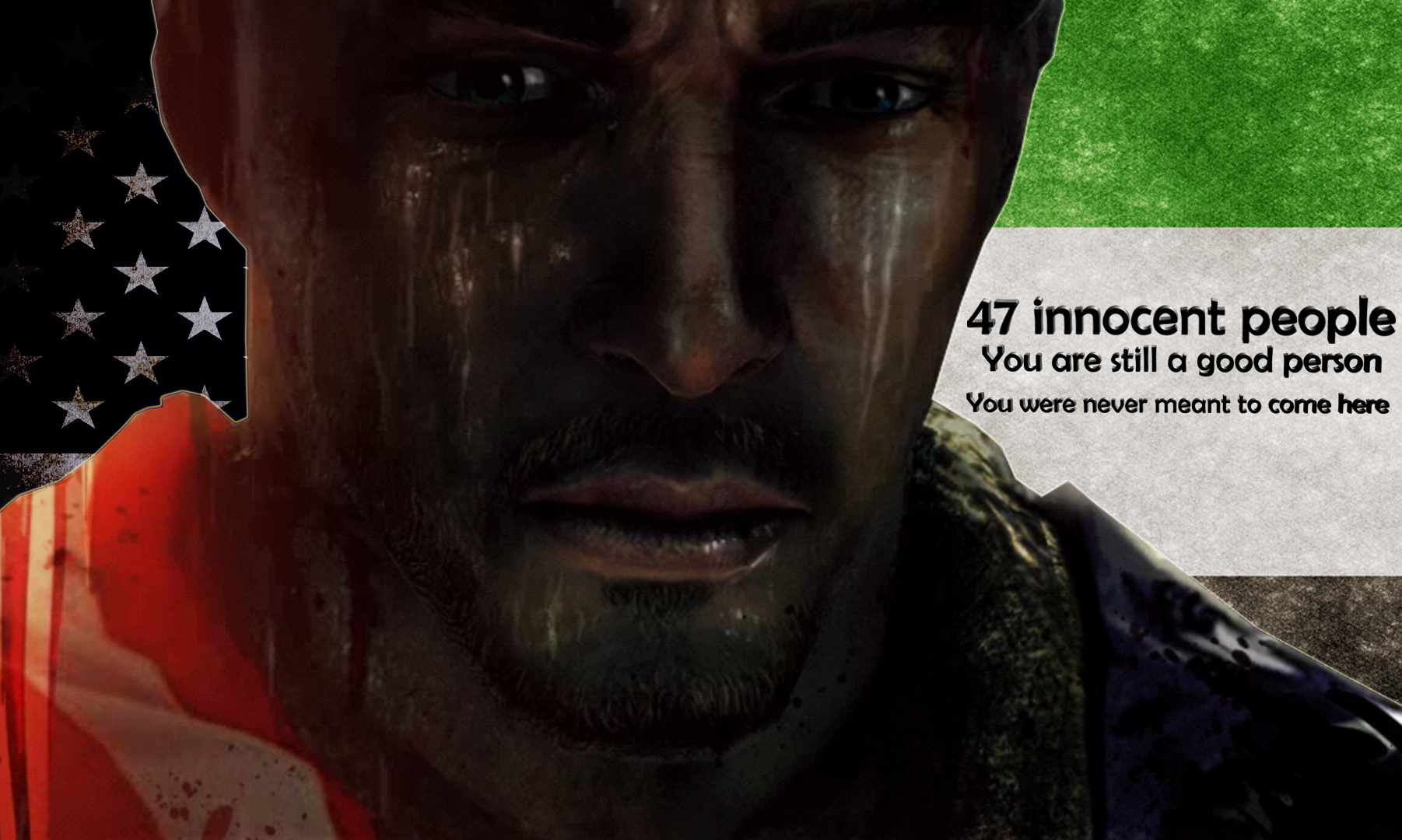

It’s been used to criticise video games ever since Clint invented it, and occasionally to even praise them (in the case of Spec Ops: The Line). The term, when broken down to the bare bones, is designed to represent when a game’s narrative and its gameplay are at odds with one another creating dissonance. It’s actually an interesting read, I encourage a look if you fancy it! But it’s a term that has plagued video games and their designers since it was originally coined way back in 2007.Ĭlint Hocking, game designer for a swathe of companies from Valve to Ubisoft, used the term ‘ludonarrative dissonance’ in his long form critique of FPS horror titan Bioshock developed by 2K. It’s a long term, probably reading like two needlessly complex words put next to each other. We still have CoD and Battlefield, after all, even if their specific focus has shifted away from “modern American military fighting terrorists and the like in far/middle eastern or former soviet places”.Ludonarrative dissonance. “thing bad” is never an especially poignant stance, but the piece does speak beyond that, and even as the genre it critiques fades more and more into the past, the ponts behind it are still relevant. But I think that’s what makes Spec Ops: The Line all that much more special- it essentially weaponises the language of military shooters in order to make a statement that the fantasies they portray are as poisonous as the crimes they fail to discuss. It’s an inherently counter-intuitive type of product when the goal is to make money, as the very premise relies on players to understand and reflect on concepts and tropes of the genres they experience. Deconstruction is not a common thing in triple-A games which I’d argue Spec Ops: The Line counts as- it was published by 2K not long before they also put out Borderlands 2 and not long after Civilisation V and Bioshock 2 (…and also Duke Nukem Forever).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)